Syllabus

English 589 A: Rhetoric and Composition Theory and PracticeMW, 9:00am-11:50AM, LN2401Robert Danberg, PhDCoordinator, Campus Wide Writing SupportTu3Crdanberg@binghamton.edu

Course Description:

English 589A prepares graduate students to teach first-year writing at Binghamton University and beyond. It introduces the contemporary theories that support informed writing pedagogy and provides an overview of major composition theories and research-based instructional practices. In sum, the seminar gives you the knowledge necessary to teach a college-level writing course, design writing components courses within your disciplines, provide you with a historically grounded understanding of rhetoric and composition studies, and offers a pedagogical scaffolding you may apply to any course in English studies. In addition, the course will provide you with the theoretical and practical approaches to teaching and learning by asking you to analyze your own writing practices and disciplinary development.

Learning Objectives

At the end of the course, students should be able to

- Propose a HARP 101 course in their field of study

- Design a writing assignment for the HARP 101 class with assignment description, objectives and rubric based on best practices of composition and writing across the discipline presented in class.

- Assess Writing 111 assignments and course material in terms of threshold concepts

- Prepare and deliver descriptions and introductions of WRIT 111 assignments intended for undergraduates

- Create a set of ground rules for productive classrooms

- Compose a Teaching Philosophy within their discipline

- Interpret their experiences as writers, teachers and students by creating an autoethnography based on course concepts related to literacy, teaching and learning

- Respond to student essays using minimal marking at two stages, response and evaluation

- Construct informal writing assignments to support course goals

- Design peer review worksheets and assignment rubrics

- Identify course learning objectives as they are fulfilled by course assignments

- Formulate a writing schedule based on the principles of constancy and moderation

- Analyze professional or graduate school genres required as part of their educational and professional development

Required Texts:

- Adler-Kassner and Wardle, Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies ISBN:978-0-87421-989-0

- Bean, Title: Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in Classroom ISBN:9780787902032 (2nd Edition)

- Boice, Robert, Professors as Writers: A Self-Help Guide to Productive Writing ISBN:978-0913507131

- Ambrose, Susan, et al. How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching ISBN:978-0470484104

- PDFs posted on Course Website

- Grounds for Argument

Coursework:

- Weekly Writing: Each week you’ll produce 500 to 100 words of text in response to prompts related to the week’s reading. This work will contribute to your final project, the Autoethnography.

- WRIT 111 Observation Report: PhD students must observe the equivalent of one week of WRIT 111 class sessions. It is up to you to approach two different instructors. Complete the observations by 4/14. Observation guidelines will be posted on our course site. Submit your write-up with a week of your observations.

- Professionalization Presentation: Create a five-minute informational presentation for an audience of first and second-year graduate students in your department. Imagine that they are attending a second and third-year orientation event sponsored by the Graduate Student Organization in your department. You have three options to choose from for the subject of your presentation. At the presentation, submit an outline of your talk, along with a handout.

- Leading Discussion: You may be paired up with a partner and expected to lead discussion for a particular day. Your partner and date will be assigned. You should prepare something engaging for class…that means something that will get us talking about the reading or considering it from different perspectives or doing something with it. Your activity should be thoughtful and elicit our participation. You don’t have to focus on explaining the reading to us, but you should be able to encourage a good discussion based on the reading. You should email me the night before with a short description of what you are going to do or the questions you are going to cover.

- WRIT 111 Coursework: Each student in the class will be expected to complete an original polished draft for each of the major assignments in WRIT 111 according to the assignment overview handouts. We will have workshops and a decompression session for each of these assignments. We will also do some norming by reading and grading sample papers.

- WRIT 111 Lesson Plan Presentation: Using course readings as well as inspirations from colleagues, favorite teachers, and your own pedagogical imagination, design classroom activities for a one-hour class period; your activities should be geared to one of the three common assignments in WRIT 111 (Personal Essay, Op-Ed, or Researched Argument) In your plan, provide a description of your learning goals for the class period, an overview of activities for the day, and any handouts or teaching materials you will provide for students. You will have 10 minutes to present your plan to our class.

- Composition Teaching Philosophy: You will develop a working Composition Teaching Portfolio. Although you may not be able to complete one, you will initiate the components and draft a structure to contain other parts as they become available. Philosophy of Writing Instruction of 350 to 500 words.

- Autoethnography: Autoethnography is an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyze (graphy) personal experience (auto) in order to understand cultural experience (ethno) (ELLIS, 2004; HOLMAN JONES, 2005). This approach challenges canonical ways of doing research and representing others (SPRY, 2001) and treats research as a political, socially-just and socially-conscious act (ADAMS & HOLMAN JONES, 2008). A researcher uses tenets of autobiography and ethnography to do and write autoethnography. Thus, as a method, autoethnography is both process and product. [1] (Autoenthnography: An Overview Ellis,Adams and Bochner) You’ll produce an autothenography of 1,500to 2,000 words. We’ll be discussing this in more detail in the coming. For background, you might skim the following. Autoethnography (Sally Denshire). Autoethnography: An Overview (Ellis, Allen and Bochner).

Policies:

Professionalism: I expect you to develop a strong ethos in the class by developing Academic integrity. You must follow BU’s Honesty Code. Documents should be submitted in MLA style.

Attendance and Late Work: Regular attendance is mandatory. Don’t miss unless you can’t avoid it due to exceptional circumstances. If you will not be in class, notify me and turn in any work due in advance. Under most circumstances, I do not accept late work.

Participation: All students are expected to come to every class on time and fully prepared to join in the conversations and activities. I reserve the right to lower a student’s course grade for being consistently absent, late, or unprepared. Adequate participation includes coming to class with all reading materials, finishing assignments on time, and participating in conversations during every class period. Further, I encourage you to reflect on your communication style and the needs of others. This means being aware of when you should actively participate or remain silent (for some time) so others can speak or when you may need to encourage input from other classmates.

Final Portfolios: due via Google Drive, Monday, May 15th, by 11:59 PM

Weekly Schedule

Note on Writing: We’ll do several kinds of writing for class. There will be formal and informal writing assignments, as well as presentations, planning documents, and preparatory notes. Each week, I’ll give you several different writing prompts intended to develop the dialogue between the reading we do and the material we read or discuss in class. Each week you’ll compile your written work in a submissions folder in the class google drive and bring hard copies to class with you. This work will become the basis for a longer piece you will write, the Autoethnography. See Submitting Your Weekly Writing for more detailed instructions. 1/30

Read:

- Naming What We Know (NWWK): “MetaConcept: Writing is an Activity and a Subject of Study, (15-16); “Writing is a Social and Rhetorical Activity,” “ Writing is a Knowledge Making Activity,” (17-20), “Writing is Informed by Prior Experience,” (54-55)

- Professors as Writers (PWB) “Why Professors Don’t Write,” “The Phenomenology of Writing Problems,” “Assessment of Writing Problems,” p. 1-38

- How Learning Works, “How Does Students Prior Knowledge Affect Their Learning,” p. 10-39

- Engaging Ideas (EI) (1-10)

- WRIT 111 Syllabus, PRN, Annotated Bibliography, Proposal, ARE, POP Assignment Sheets

Pick up:

WRIT 111 Course Documents: Syllabus, Assignment Documents– Pick up at LN 2411

Write:

- Complete the Assessment in Chapter 3 of Professor’s as Writers.

Once you’ve completed it, write a short description of what you discovered along with any initial response.

- 200 to 250 words: How do high school and college students learn to write, what should they be taught and how should they be taught?

- Summarize the PRN, Annotated Bibliography, Proposal, ARE, POP Assignment Sheets (25 to 75 words; bullet points acceptable along with lists of keywords; think in terms of what you consider the essential points for students; feel free to use fragments and commands, for example, Write a…X to Y pages, MLA format…)

- 200 to 250 words: What beliefs or experiences do you think shape how first-year students approach college writing? What obstacles do students face?

2/6

Read:

- NWWK: “Writers Histories, Processes, and Identities Vary” (52-54);” “Disciplinary and Professional Identities are Constructed Through Writing”(55-57); “ Writing Provides a Representation of Ideologies and Identities” (57-59),

- EI- “Informal, Exploratory Writing Activities ” (120-145)

- “What is Literacy?, “Inventing the University” (PDF– Literacy/Invention)

Write:

- Inventory upcoming writing projects and writing related projects that are self-generated or due as part of your current coursework: 75 to 100 words

- Pages 131 to 145 of Engaging Ideas lists 22 ways to incorporate exploratory writing into a course, along with some suggestions about how you might assess or evaluate it (checks, numbers, etc.) Review the two week period that encompasses the PRN. Develop a set of exploratory assignments. Try to come up with at least one assignment for each class period that moves the process of the PRN forward and one assignment to write between class periods. Describe how you might respond to assignments if you collected them. Think of what students would do with them if they were to share them in groups or pairs with classmates.Speculate on a strategy for assessment that you might use based on Bean’s suggestions.

- Timeline of Writing Transitions: 200 Words that describe the major transitional moments in your writing life; you can focus on a number of different transitions or elaborate on one or two major transitions

2/13

Read: Engaging Ideas, “Formal Writing Assignments,” (89 to 120)

Learning (Teaching) to Teach (Learn) Malea Powell, PDF Powell/Bullock in our Drive Folder. Axehandles; Elliot Eisner, What Can Education Learn From the Arts About the Practice of Education?

Professionalization Presentation Assignment Sheet

Observation Assignment Material

Write:

- Select three quotations from each of the week’s readings. Upload them.

- PRN: Upload a copy of yours to our Google Drive Submissions folder. Be sure to have a copy available (hard or virtual).

2/14

Send me an email that tells me whose classes you’ll be observing.

2/20

Topic: The Annotated Bibliography

Reading:

Assignment Material and Schedule: Annotated Bibliography (Note any questions and concerns you have about the assignment)

PDF: Skiing as a Model of Instruction; Situated Cognition (Structuring activity, p. 36-7, Apprenticeship and Cognition through the end of the essay, p.39-41)

NAMING: Writing Speaks…Forms (35-36), Genres are Enacted/Writing is a Way of Enacting (37 to 40)

EI- Formal Writing Assignments (95-100)

- Articulation of Learning Goals as Preparation for Designing Assignments

- Planning the Course Backward by Designing the Last Assignment First

- Best Practices in Assignment Design

EI- Helping Students Read Difficult Texts (161)

- Causes of Students’ Reading Difficulties

- Suggested Strategies for Helping Students Become Better Readers

- Developing Assignments that Require Students to Interact with Texts

EI- Designing and Teaching Assignments to Teach Undergraduate Research (224)

- The Complications of Research Writing

- Creating Short-Meaning Constructing Assignments

Writing:

Note Taking Strategies: Use the Note-Taking Strategy Instruction Manual (in the course guide) for Engaging Ideas; Type up five quotes from the across the PDFs and Naming.

Triptych

Powell and Snyder describe layers of interaction as part of the process of learning and how each situates them as teachers, learners and writers. Eisner talks about the particular ways that knowledge can be understood as part of participation in the arts and how that understanding can influence our thinking about education. Today’s readings on apprenticeship, disciplinarity and instruction point towards ways to articulate, in terms of instruction, some of the ideas found in last week’s work by Powell, Snyder, and Eisner.

Write a two hundred fifty word triptych (See Samuel Dinnerstien: The Fulbright Triptych. Make one part situate you as a learner or teacher in a non-academic subject; make a second “panel” situate you as a learner or teacher in an academic scene; in the third and last part, meditate on– or imagine– your identity and principles as a teacher designing instruction. See video below:

For referencetrip

Additional Annotated Bibliography Resources Resources:http://www.rebeccamoorehoward.com/adopters

http://chuma.cas.usf.edu/~runge/Class_Bib.htm

2/27

Topic: The Proposal

Read

The Proposal Assignment Sheet and Material (Note any questions and concerns)

Autoethnography: An Overview Ellis,Adams and Bochne

http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1589/3095

Sally Denshire, Autoethnography

Click to access Autoethnography.pdf

EI- Coaching the Writing Process and Handling the Paper Load (290-299)

- Designing Good Assignments,

- Clarify Your Grading Criteria,

- Build in Exploratory Writing or Class Discussion to Help Students Generate Ideas

- Have Students Submit Something Early in the Writing Process

- Have Students Conduct Peer Reviews of Drafts

Write:

Instruction Manual Technique for EI 290 to 299

After reading the two pieces on autoethnography, complete the Autoethnography Assignment Sheet Assignment in our course guide.

3/13

Read:

Norming: In our folder, you’ll find a folder called “Norming: Annotated Bibliography”. There will be three annotated bibliographies to read. You’ll use the rubric. Use the instruction sheet in the folder.

Write:

Bread Project: Follow the link for instructions.

3/20

Professionalization Presentation:

- Sarah Sassone

- Danielle Schwartz

Read:

- Designing and Sequencing Assignments to Teach Undergraduate Research, Engaging Ideas, 224 to 235 (Use Instruction Manual Technique)

- How Learning Works, Chapter 4, How Do Students Develop Mastery? (Choose 5 quotes)

- Supplemental Faculty Guide Assignment. Found at this link. (List questions and concerns)

- ARE Assignment Sheet and Sequence (List Questions and Concerns). Found at this link in our folder.

- Final Schedule found at this link. Complete the Survey Monkey survey.

Write:

Complete the Second Part of the Auto Ethnography Assignment. Found at this link in our folder.

Move: To complete the second part of the auto ethnography assignment, you need to move your first draft to a folder where your colleagues can see it.

- To copy and move your auto ethnography draft to the Sub Auto Eth folder, do the following.

- Open your document.

- Go to File in the menu bar and choose <Make a Copy>. Then, name and save the file.

- Once you have the new file, go to File in the menu bar and choose <Move to>. On the bottom of the pop up, you’ll see a blue square <Move this Item>. Choose it and then, select the folder <Sub Auto Eth>.

Norming:

- Annotated Bibliographies from 3/13

When you go to the website, look under “lessons”. I’d like the site to give us some shared language for talking about argument, which will be helpful when you talk to your students next year. I consider these soft deadlines. I’d like you to finish the “GfA” assignments gradually over the course of the rest of the semester keeping pace with these deadlines, work at your chosen speed.

- Why Do We Argue

- The Five Parts of an Argument

In Class Schedule:

Something I want to improve is management of class time and moving the class toward group and project work. Based on the the schedule for 3/20, this is my projected organization for work in class. My goal is to complete all of the following. It’s especially important given the fact that we’ll be shifting to regular project work and norming.

9:00 to 9:45

- Norm Annotated Bibliography Assignments

9:50 to 10:20

- Problems, Questions and Concerns: Reviewing the Researched Argument Assignment

10:20 to 10:30

- Break

10:30 to 10:40

- Review Auto-Ethnography Peer Review Assignment

10:45 to 11:15

- Professionalization Presentations with Sarah Sassone and Danielle Schwarz

- Continue Work on Alternate Drafts of Presentation Rubrics

11:20 to 11:50

- Supplemental Course Guide Project Groups

3/27

Professionalization Presentation:

- Johanna Bermudez

Read

- Designing and Sequencing Assignments to Teach Undergraduate Research, Engaging Ideas, 235 (Bottom of Page) to 252 (Use Instruction Manual Technique)

- Using Small Groups to Coach Thinking and Teach Disciplinary Argument 183 to 201, Engaging Ideas

- How Learning Works, Chapter 5, What Kind of Practice and Feedback Enhance Student Learning? (Choose 5 quotes)

- POP Assignment Sheet and Sequence (Note questions and concerns)

- Proposal sample in folder

Write:

- Short Proposal for your group– Supplemental Guide

- Proposal response

Grounds for Argument

- Claims

- Evidence

4/3

Professionalization Presentation

Dylan Cheek

Supplemental Guide Assignments

- Groups will announce reading and writing assignments for classes on 4/24; 4/31; 5/4

Read:

- Dealing with Issues of Grammar and Correctness, EI, p.66

Blog: (Post on the Bread Blog by Saturday 11:59 PM)

- Share your experiences having your work graded

Grounds for Argument

- Acknowledgement and Response

- Warrants

Class Plan

- 9:00 to 9:30: Professionalization Presentation

- 9:30 to 10:30: Argumentative Research Essay/POP (Questions and Concerns) We’ll review the assignments as we did in our last class, critiquing the assignment and looking for areas for us to prep around in teaching it. We’ll do them with respect to one another

- 10:30 to 10:40: Break

- 10:45 to 11:15: Ideas about Grammar and Correctness. The focus on of our work will be the principles that can guide how we choose to respond to issues of grammar and correctness when we respond to student work. This will be a discussion. I’ll be relying on the blogs to help me focus our conversation.

- 11:15 to 11:50: Guide Groups. In the last five to ten minutes of class, we’ll groups will add their assignments to our Course Guide.

4/10 BREAK

4/24

Professionalization Presentation:

Kazuki

Supplemental Guide Class Discussion/Workshop:

Group 1

- Read Engaging Ideas pp. 17-24 and 186-9

- Re-read opening of Powell’s “Learning (Teaching) to Teach (Learn)” pp. 571-3

- Read through our group’s process documents on the PRN and bring questions, concerns, and suggestions (document will be uploaded to the 589 folder and labeled “Supplemental Guide – PRN”)

Read:

- Writing Comments on Student Papers, Engaging Ideas, 290 to 316 (Use Instruction Manual Technique)

Write:

- Draft: Auto Ethnography

Comment:

ARE Comment: I’ll supply you with an ARE (argumentative researched essay) to read. Print it and comment on it so you can submit it to me.

I’d like you to comment on this paper as if you’d be giving it to the student. Read the EI Chapter on Writing Comments on Student papers. I’d like you to follow his principles. Refer in particular to

- The minimal marking technique described on pages 82-84 and 330-331 for dealing with error.

- The suggestions for writing end comments on page 333.

- The review of general principles on 334-336

When you provide your end comments, use the language of the rubric. It will form a common language between yourself and the student and yourself and your pedagogy group members.

You’ll notice that in Bean’s approach to grading, he doesn’t put a grade on the text under revision. In WRIT 111, we often include a few sentences that answer the question, “What grade would this earn using the rubric we use.” This is not the emphasis of the comments and only meant to provide students with a way of interpreting the assignment. We’ll address this directly in class, so you do not have to include such a paragraph. However, when you’re commenting on higher order concerns, keep the rubric close at hand to help you define the

5/1

Supplemental Guide Class Discussion/Workshop:

Led by Group 2: Prior Reading

- Bean – Engaging Ideas, pg 170 what it says/what it does , pg 170-173, Chapter 4 – Teaching alternative genres

- Naming What We Know: Pg 20 Writing Invokes, pg 48, pg 8 & the two linked example of ‘A’ POP’s. Be prepared to discuss feedback of your findings.

Read:

Using Rubrics Engaging Ideas, 267 (Use Instruction Manual Technique)

Write:

- Peer Review Activity: Auto-Ethnography

Comment:

- POP (See instructions for last week). Sample located here. In our folder under “POP May 1”.

Supplemental Faculty Guide:

To help clarify what you should show us on the last day of class, I’ve created a sample in a file called Supplemental Guide, which you’ll find in the Supplemental Faculty Guide Assignment folder.

As described in the assignment sheet for the Faculty Guide, the process has two parts, a discussion with the class that introduces your plan and materials. The purpose there is to open the floor to talk about the basis for your suggestions and how they work in terms of what we’ve learned about best practices.

The second part of the process is to produce finalized materials for the use by teachers outside (and inside) the class– the actual guide itself. The guide will contain handouts, a description of how to use and introduce activities and handouts. If handouts are in PDF form and can’t be inserted into the document, there will be a folder for links.

We’ll review the guide in class and talk about how to prepare the material before you post it. The material you show us on the last day doesn’t necessarily have to be complete, but the framework should be. For instance, you may not have completed the handout, but is contents should be clear.We’ll also talk about how to format in Google docs.

5/4

Read:

Writing Program Administrators Frameworks for Success in Post-Secondary Writing

Write:

Write one fifty to two hundred words that does any or all of the following:

- Answer the question, Is it possible to develop a “habit of mind” in a semester long writing course?

- Where is knowledge of a “habit of mind” located? For example, is it something we are told? Is it something developed through practice? Do we ever call upon it consciously? Is it only instinctive?

- Do you think the Habits of Mind in the Frameworks for Success are fairly accurate? Can they be more particular to the conditions of writing? Would you add any?

Supplemental Guide Class Discussion/Workshop:

Led by Group 3:

- Engaging Ideas: Bizup “BEAM,” Pg. 23. Annotate your understanding of each of the categories in the BEAM chart.

- Engaging Ideas: Chapter 13, Pg. 241-244, Bean’s discussion on scaffolding

- “Grounds for Argument” Handout: “From Grounds for Argument: The Five Parts of an Argument”

Comment: Annotated Bibliography In our folder under May 4 AB(See instructions for last week)

5/8

Present your Part of the Course Guide.

Read the documents in the Plagiarism Folder in our Course Google Drive Folder. You’ll find a paper with a turnitin report. You don’t have to read the paper– just look over the report. For a bit of cultural context, read this Atlantic piece .

Submitting Your Weekly Writing

In our Google Drive Folder, you’ll find a folder called “Submissions”. In it, you’ll create a folder for yourself called “Last Name Submissions” (Example, Danberg Submissions).

Unless otherwise instructed, each week, you’ll create a new document for the week’s writing. Give the document the name “Last Name Month Day” (Example, Danberg Jan. 30).

In each document, give each writing assignment its own page. At the top of the page, type the question or task. For example, Danberg Jan. 30 will have four separate pieces of writing, each beginning on a new page.

- Assessment in Chapter 3 of Professor’s as Writers.

- How do high school and college students learn to write, what should they be taught and how should they be taught.

- Summary of assignment sheets

- What beliefs or experiences do you think shape how first year students approach college writing?

Auto Ethnography Assignment Sheet Assignment

Autoethnography is an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyze (graphy) personal experience (auto) in order to understand cultural experience (ethno) (ELLIS, 2004; HOLMAN JONES, 2005). This approach challenges canonical ways of doing research and representing others (SPRY, 2001) and treats research as a political, socially-just and socially-conscious act (ADAMS & HOLMAN JONES, 2008). A researcher uses tenets of autobiography and ethnography to do and write autoethnography. Thus, as a method, autoethnography is both process and product. [1] Autoenthnography: An Overview Ellis,Adams and Bochner

Autoethnography is ‘an alternative method and form of writing’ (Neville-Jan, 2003: 89) falling somewhere between anthropology and literary studies. Some social science researchers have an interpretive literary style and others have been ‘trained to write in ways that use highly specialised vocabulary, that efface the personal and flatten the voice, that avoid narrative in deference to dominant theories and methodologies of the social sciences’ (Modjeska, 2006: 31). The complex relationship between social science writing and literary writing has led to a blurring ‘between “fact” and “fiction” and between “true” and “imagined” ’ (Richardson, 2000b: 926).

Autoethnographers often blur boundaries, crafting fictions and other ways of being true in the interests of rewriting selves in the social world. Writing both selves and others into a larger story goes against the grain of much academic discourse.Holt foregrounds the challenge that autoethnographers issue to ‘silent authorship’: By writing themselves into their own work as major characters, autoethnographer have challenged accepted views about silent authorship, where the researcher’s voice is not included in the presentation of findings. (2003: 2) Sally Denshire, Autoethnography

Assignment Instructions(Revised 2/21)

Autoethnography Assignment After reading the material on autoethnography, create a draft of an assignment sheet for autoethnographies for our class. My goal is for you to use this non-traditional academic genre to connect our investigation into teaching, learning, and writing with your own experiences and practices as a teacher, learner and writer. The final result should demonstrate your engagement with key concepts in our work that can illuminate your approach to teaching and experience of writing and learning.

Below I’ve included readings that talk “about” autoethnography and examples of autoethnography. I suggest that you look them over, then choose two or three to read to help you construct the assignment.

Use the assignment sheet examples you find in the reading in Engaging Ideas. Your assignment sheet should be no more than 250 words. The assignment you draft should be based on the components of good writing assignment as described in the text, as well as the concept of RAFT/TIP. Keep track of any “Am I doing this right?” questions that emerge as you make choices. In addition to the assignment sheet, include the following material:

- A short explanation of the assignment you might read to our class that explains your assignments goals and challenges. (200 words, tops)

- A description of interactive components that might precede the assignment. (Explain each of them in a few sentences to a paragraph– what your idea is, what someone would do, what the purpose is, who would respond, what kind of response.

- A description of the components of a rubric you might include. While you don’t have to create a full blow rubric, using the examples in the text as a guide, sketch out the main categories you might include along with some components of them. You might start the process by describing a “B” version, then abstract characteristics from your description as a set of categories and descriptive bullet points. (100-150 words)

On the Genre:

Autoethnography: An Overview Ellis,Adams and Bochner http://www.qualitativeresearch.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1589/3095

Sally Denshire, Autoethnography http://www.sagepub.net/isa/resources/pdf/Autoethnography.pdf

Examples:

Sometimes I am afraid: An Autoethnography of Resistance and Compliance

Writing the Self Into Research

Professionalization Presentation

Overview: Create a five to ten minute informational presentation for an audience of first and second-year graduate students in your department. Imagine that they are attending a second/third-year orientation event sponsored by the Graduate Student Organization in your department. You have three options to choose from for the subject of your presentation. At the presentation, submit an outline of your talk, along with a handout.

Audience: First and second-year graduate students in a professionalization workshop held by the department’s Graduate Student Organization.

Deadlines: February 20, Class time. Send me an email describing the topic you intend to present on and be prepared to discuss your plans in class.

Sign up to present during the last two weeks of March and the first two weeks of April. I will let you know when the sign-up sheet is posted. We will have two to three slots per class session.

Instructions: Choose one of the following topics for your presentation.

- Research the journals in your field or genre. Compile a list of five journals at different tiers, including the top tier journals and journals in which graduate students and early career academics publish. Choose one journal and review two years of contents. Inventory the topics and the authors, as well as the editorial. Choose an article resembling one you that you might write for publication.

- Research the conferences in your field. Compile a list of five at different tiers, including top-tier graduate students conferences. Review the Calls for Proposals for upcoming and last year’s conferences. Look for information about successful presentations.

- Research the documents required for acquiring your degree– exams, dissertation prospectus, dissertation. Read the documents your department has produced, find examples, discuss the process with people who have gone through it.

Submit an outline of your presentation to the instructor. Prepare a brief informational handout for your colleagues and instructor. The handout should contain key information they can use to make decisions about their own work.

Class Observations

You’ll be asked to observe a WRIT 111 class this term. As a rule, observations are best done between the fourth and eleventh week of class, (essentially, giving the class the first three weeks to pull itself together and the last three weeks to finish up). Below you’ll find a list of instructors I’d like you to choose from. These are all experienced WRIT 111 instructors. The list doesn’t include teachers in their first year.

You’ll sit in on class. I’ll have some material to complete– notes to take and a short reflection to submit following the class. You’ll find the forms below.

You’ll contact the teacher via email and explain that you are in 589 and would like to observe a class. Ask the teachers when it might be a good time to observe. After the observation, arrange for a follow-up appointment with the instructor to ask any questions you may have about the class, the curriculum, or teaching in general. Meet at their convenience– shoot for their office hours if you can.

You’ll find forms to use for your observation at the following link: Focus on Learning– Peer Observation

Below you’ll find the 111 Course Schedule so that you can find classes when you can observe. Ask one, but have at least two teachers in mind– we don’t want to overload people. If they’ve had several requests, it’s okay for them to pass.

Send me your observation date by February 10. Complete the observations by 4/14.

Teachers:

- Natalia Andrievskeh

- Barrett Bowlin

- Sarah Bull

- Jessica Femiani

- Trish Farco

- Angie Pelekidis

- Kerstin Petersen

- Vanessa Jaeger

- Doug Jones

- Paul Shovlin

- Sean Fenty

Note-Taking Strategy: Instruction Manual

Instruction Manual

This is an informal writing assignment/note-taking strategy that wants students to make selections based on significance– the value is “purpose”. I prepared it for a specific moment in class, as you might. With respect to our class, you might revise this mentally to think about how the reading is meant to guide you in some teacherly decision-making. If you were to take the principles and observations at face value, which would you find most useful in practice? The notion is to use the idea of an audience and genre (instruction manual) as an enabling constraint. Say it clearly and plainly, be concise, allow yourself to refer to the original text, and so on. Students can treat notetaking along a continuum between writing down everything without sorting to only writing down responses or attitudes to the subject matter, the task suggests an approach that incorporates criteria for selection with an audience that values brevity and clarity.

As I mentioned in class, you often read with a purpose in mind, so your note taking should serve that purpose. Throughout the semester, I’ll assign you reading from the Norton Field Guide that will provide you with tools, principles, methods and strategies you will need to complete the project.

“Instruction Manual” is a simple note taking technique. You use it when you’re trying to find a practical solution to a tangible problem. For example, you’ll be asked to read a few pages on completing a Working Bibliography. You need to know how to create a Bibliography– what it contains, what it’s for, and so on. After you read, do the following.

Instructions:

Pretend your notes will form the basis of an instruction manual. In the case of the working bibliography, a set of instructions to be used to create a working bibliography. You will use this as a reference. Make a bulleted list, each consisting of not more than two sentences, that instruct you in what to do or not do, and provides you with any definitions you need or things to watch out for. It can look like the following, for example.

- To complete this exercise, you have to imagine that someone other than yourself with reference to these instructions.

- You have to choose the most significant items.

- You need to be concise and direct. Use command forms if you want.

- If you use any special phrase directly from the reading, put quotes around it so we know.

- Put page numbers at the end of the bulleted statements in parenthesis to remind us where the information came from.

- Be sure to define terms, such as “working bibliography”.

- If you see something like a long list which itself is a reference, feel free to refer the reader to the list, but explain what it’s for first, and why they should.

Note Taking Strategy: What is my initial response?

It helps make note taking more useful and efficient when we think of it as a flexible process responsive to our needs and purposes. For instance, it’s common to allow the text we’re reviewing dictate how we read. We proceed with a chapter or an essay very differently than we might if we were working with web links. We march through the piece. Experienced readers often know what not to read, or at least take the time to see what, if anything, they might need is present. But note-taking isn’t always so instrumental; we’re often just trying to lay down layers of experience with subject matter like base coats of paint. But even that analogy has its limits. If you assume from the start that once a piece is in your hands, you control the reading experience, you can read any part of it first, including the end. A better house painter than I am might begin at one corner and work her way over. But when it comes to reading, assume that, now that the text is in your hands, all that matters is the goal: what you want to take away from the experience or what you want the experience to be. Rather than think of reading as a process of collecting, or sweeping up, or combing-through, you can consider reading to be shadow boxing, a steeplechase, a belay, or a pas de deux.

In more direct terms, start where you’re at. Before you read, just down a few thoughts about why you’ve been asked or have decided to read something and what you hope to find– or what you aren’t sure you will find.

Review the piece from beginning to end so that you know how it’s laid out. Skim lightly with attention to sections, the overall construction of the piece, the relationship, say, between the first few paragraphs and the last few. Return to the beginning and read straight through. For the heck of it, decide not to stop and “take notes” but to read with a fleet and sure step. Note what to come back to in the margins or on a page.

When you reach the end, complete the following task:

Answer the question, “What is my initial response? Emotional, intellectual, psychological– how do I respond to what I’ve read?”

Once you’ve written that, trace the source of your response. Is it based prior knowledge that contradicts what is written or confirms it? do you associate the subject matter with some experience? Is your response rooted in some principle or set of beliefs or values?

Graphic: The Inquiry Process

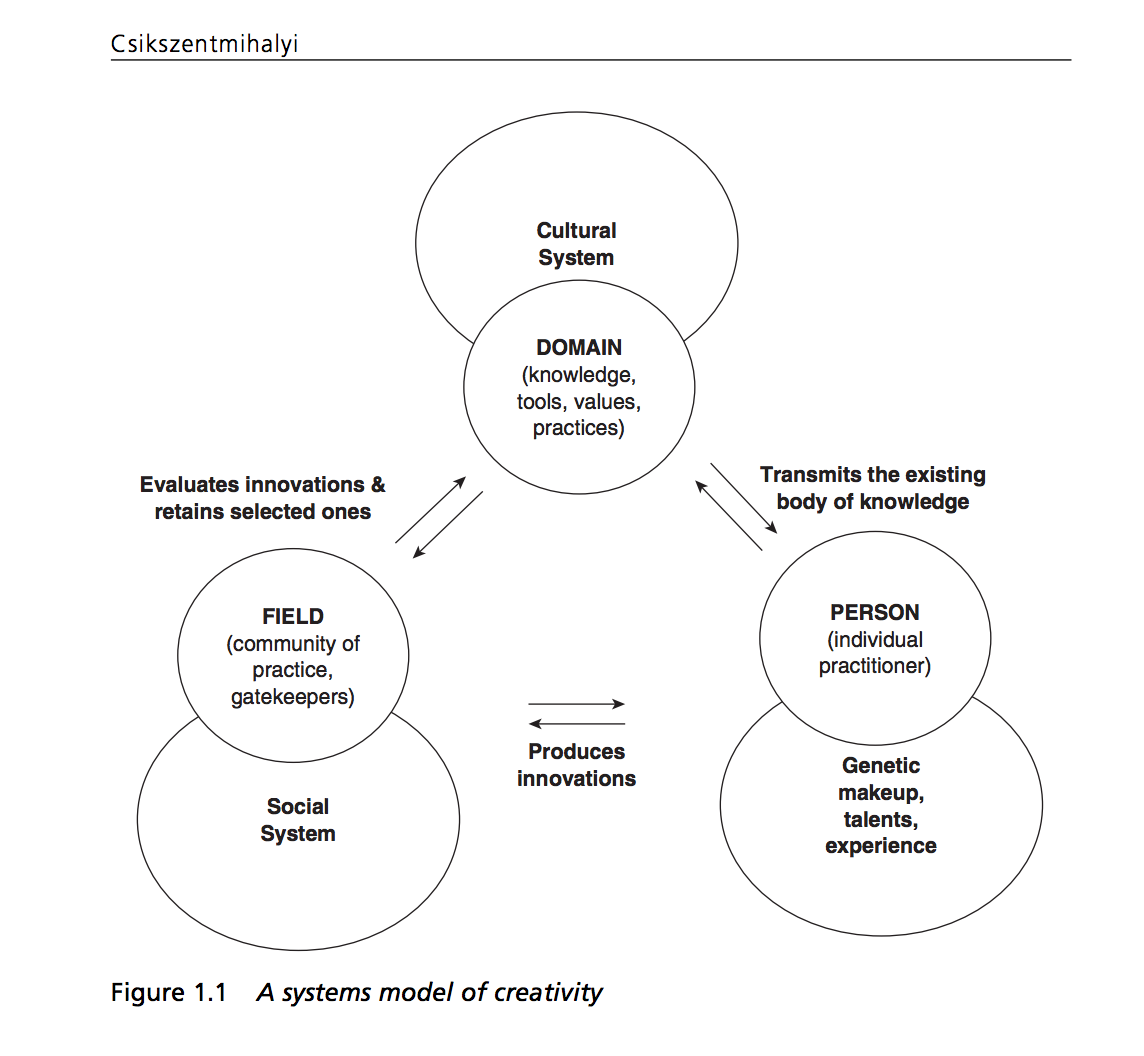

Graphic: A Systems View of Creativity

Major Deadlines

2/6

2/13 Pre-Research Narrative

2/14 Observation Arranged

2/20 Assignment Analysis: Annotated Bibliography

2/27 Assignment Analysis: Proposal

Professionalization Presentation

3/6 No class

3/13 Assignment Analysis: Researched Argument

Professionalization Presentation

3/20 Professionalization Presentation

Assignment Analysis: Public Opinion Piece

3/27

4/3

4/10 No Class

4/14 Observations Completed; Lesson Plan Presentation

4/17 ; Last Opportunity to Submit Observation Material; Lesson Plan Presentation

4/24 Draft: Auto Ethnography; Lesson Plan Presentation

5/1 Draft: Teaching Philosophy; Lesson Plan Presentation

5/8

Assignment Analysis: Supplemental Course Guide

Assignment Analysis: Supplemental Course Guide

Collaborate:

Introduce the assignment to colleagues

- Where does it fit into the outcomes for WRIT 111

- What does the student need to know to be able to complete the assignment successfully?

- What is its place in the whole course?

- How does it connect to work students might do in other courses?

- What gaps do you anticipate students may have in their ability to complete the assignment?

Each group member:

Create a brief introductory talk for the students on the assignment. This can include some of the information from above. Include some of your own experience as a writer or learner, particularly how this might play out in your own discipline and where it can fit into their own work.

As a group, decide on three– collaborate or as an individual:

- Create a small group class activity that introduces some aspect of the assignment to assignment to students

- Create an annotated Model Text for students to refer to with a screencast.

- Create a short annotated bibliography of

- ‘supplemental material that teachers can use to understand how to teach the assignment or that students can refer to do the assignment

- Create a small group activity focused on reading texts

- Create a lesson Plan for a single week

- Create a peer review activity

- Create a collaborative activity for students

Grading

Weekly Writing and Notetaking 20 points

Professionalization Presentation 20 points

Autoethnography 20 points

Course Guide Presentations and Materials 20 points

Observation Material 20 points

———————————————————————

Weekly Writing and Note Taking

Each week there’s a writing/note-taking assignment. You can miss two week’s assignments. You need to be prepared for class, but don’t need to complete the note-taking. Assignments you can’t miss include grade norming or grading practice assignments.

Professionalization Presentation

Autoethnography

Course Guide Presentation and Materials

Observation Material

When I evaluate each of the above assignments, I consider the following:

- Adequate: Produced the minimum requirements for the assignment as described in the assignment material.

- Competent: Demonstrates the ability to respond to the requirements of the assignment, show thoughtfulness in use of course concepts and make connections between materials

- Professional: Includes characteristics of adequate and competent work.Demonstrates an effort to analyze, reflect upon and integrate course work into one’s own practice, as well as to create material that looks outward toward future work.

Bread Assignment

Sesame Flatbread from Serious Eats

Calls for sesame seeds but doesn’t need them. Salted Honey butter also optional, but, do yourself a favor, try it. I make pizza with flat bread. It’s a straightforward bread to try, although as with anything this apparently straightforward, it shines when made people who understand its nuances.

http://sweets.seriouseats.com/2014/02/wake-and-bake-sesame-flatbreads-with-salted-honey-butter.html

Tassajara Bread Book

This pdf has the recipe for bread using the sponge method. It also includes ways to shape the bread. You don’t need bread pans. You can shape it into a round loaf on bake it on a cookie sheet.

This is a King Arthur Company recipe. It calls for Xanthan Gum, which you can find in the Johnson City Wegmans. It also calls for an electric or stand mixer, but lacking that, try it by hand and see what happens.

Joan Nathan’s Challah Recipe is reliable and she’s an institution. You can find plenty of video on her on YouTube. Braiding Challah challenges me– three strands is my “go-to”. But you can find video showing you how to do more intricate braids than that.

This is the bread I’m going to try over the break. It calls for a stand mixer and a dough hook. I have neither. The mixer makes less work, sure, but doing without doesn’t make more work.

Proposal Peer Review and Response

In our 589 Google Drive folder (in a folder called 3/27 Sample Proposals), you’ll find a pair of student proposals and the proposal assignment sheet. The proposal is an example of a “meaning constructing” research assignment that helps students practice, in context, some of the “Difficult subskills of research writing” (See EI, 229-232).

Our exercise– your work with the proposal– is meant to do three things:

- give you practice designing a peer review activity that can improve student work prior to submitting it to you,

- lay the groundwork for our work responding efficiently to student papers.

To complete this, refer to the bottom of page 296 to 298 in Engaging Ideas and figure 15.3 on page 297.You’ll also need to read the proposal example in our folder and the proposal assignment sheet.

Instructions:

Read the section Response-Centered Reviews the bottom of page 296. Use the descriptive questions as a model to create five descriptive questions for a peer review of proposals. Then, use those same questions to respond to the student. Remember, the key here (as you’ll see in the figure) is to create questions or tasks that do not call for evaluations, opinions, or judgments.

Supplemental Guide: Preliminary Proposal

Situation: For the Supplemental Guide, you’ll develop assignment material– plans, resources, etc.– which teachers in Writing 111 can use to address some aspect of the WRIT 111 experience. There is a collaborative aspect to the guide: you’ll work with a small group to workshop your material and, perhaps, build a section of the guide depending on our decisions as a class. The first step is to offer a preliminary proposal. The document is speculative to a point– you can certainly change your mind. But it should be imagined fairly concretely as one

Task: Write a 200 to three hundred fifty words proposal for instructional or lesson material your might create. It should answer the following questions. Be sure to have it available for you to refer to in class.

- What instructional need or question do you intend to address? Explain the need or question?

- Where does it fit into the design of the WRIT 111 curriculum?

- What need will it fulfill for students and instructors? What contribution will it make to their work or understanding?

- What kind of instructional material or resources might accompany it?

- What kind of plan will you create?

- Which the books or related articles we’ve used for class will provide a basis for the way you approach the material. You can look at ahead to see something is addressed we haven’t reached yet. Explain the connection you’re making between the work we’ve read and what you’ll create. For example, you might want to create small group work that scaffolds an important element of research: the function of sources. You use Bean and Ambrose to design three in class tasks to help students ask “Determinate Research Questions” (see Bean p. 237) identify sources in terms of their function for their project ( BEAM in Bean, 239).