Your Project Notebook

Overview

Rdanberg

I think of a project like a dissertation or a book as a hike through time, rather than space. Over a course of days, weeks and months, a course that wends its way through the commitments of everyday life, we do the work of research and writing. Each week, we make choices intended to move the project forward so that we arrive at a destination that we often can’t quite picture at first, and that becomes clear as our work evolves.

A Project Notebook has become, for me, a way, over the course of the writing journey, to stay found.

In his book, How to Stay Alive in the Woods, the naturalist Bradford Angier writes that “We become lost not because of anything we do, but because of what we leave undone… For there is one method to keep from getting lost, and that is to stay found.”

He goes on, “We stay found by knowing approximately where we are at every moment, and this is not as complicated as it may seem, for any one of us can keep track of his whereabouts by means of a map, compass, and pencil.”

The project notebook works like a map and a compass.

In our class, it’s meant to help you imagine a period of time over which you’ll complete some portion of your project, to identify your goals, prioritize them, and break them down into clear, concrete actions that you map onto your available time, week by week.

The Project Notebook is also meant to help you learn about yourself– the way you set goals, use time, and plan. With that information, you can make better decisions, about how and when your work. It is a tool that helps you monitor progress. As a class, the Project Notebook provides a common reference point for our discussions about the work of writing dissertations.

Setting up the Project Notebook takes some time at first, and less and less time as it becomes part of a process of routine reflection.

In class on Friday, you’ll review the Project Notebook and update it. You’ll be able to map your goals onto time, choosing your priorities for the week ahead. You’ll also be able to use it throughout the week to craft daily “To Do” lists.

I actually have two “Project Notebooks”. One is for my work and family life, and the other is for my creative projects, In the following pages, you’ll see selections from the Project Notebook for my creative work.

Overview: The Contents of Your Project Notebook

You’ll make your project notebook out of a three ring binder divided into five sections.

Monthly and Weekly Calendars

At the front of my Project Notebook are two kinds of calendars for the period of time I have in mind. Since I work in a university, time changes every three or four months, and the work has its seasons– exams and paper grading.

The Weekly and Monthly calendars in my Project Notebook help me prioritize my goals for the week based on available time. I don’t use these calendars for keeping track of my day to day commitments. For daily time keeping, I use a google calendar.

I keep four things in mind when I review my Project Notebook to decide how to use my time each week.

- I want to assess time realistically so I set goals realistically. If I have papers to grade, I may have only a few hours over the course of the week to work, and I want to choose tasks that require less concentration than when I don’t have to grade papers. When I set goals unrealistically for the week, I end up disappointed and discouraged.

- My goal is to work consistently and in increments over a long period of time, rather than rely on having big chunks for time.

- I try not to take long breaks between work on a current project.

- I reflect weekly on what my priorities are and monitor my progress, so I can think through what to do if I’ve gone off track.

Monthly Calendars

I print out a monthly calendar for each of the months of the period I have in mind– in this case, Spring 2020.

In the monthly calendar, I note holidays, vacations, conferences, and even paper grading so that I can anticipate rhythm of my semester. If I know I’ll have grading to do, or travel, I’ll either have to pick up the pace before or after to stay on track. I can plan for sustained work that requires time and concentration for breaks.

I put my project benchmarks and deadlines in the monthly calendars.

Weekly Calendars

To track each week, I print a simple daily time grid that blocks out times I know I can’t work on my project– when I teach, commute, prep for dinner and dinner time, for instance. I make a copy for each week of the period of time covered by the monthly calendar. Then, each week, I add any other commitments that aren’t routine– appointments, and so on.

Getting Started: Setting Goals

Products, Priorities, or Goals

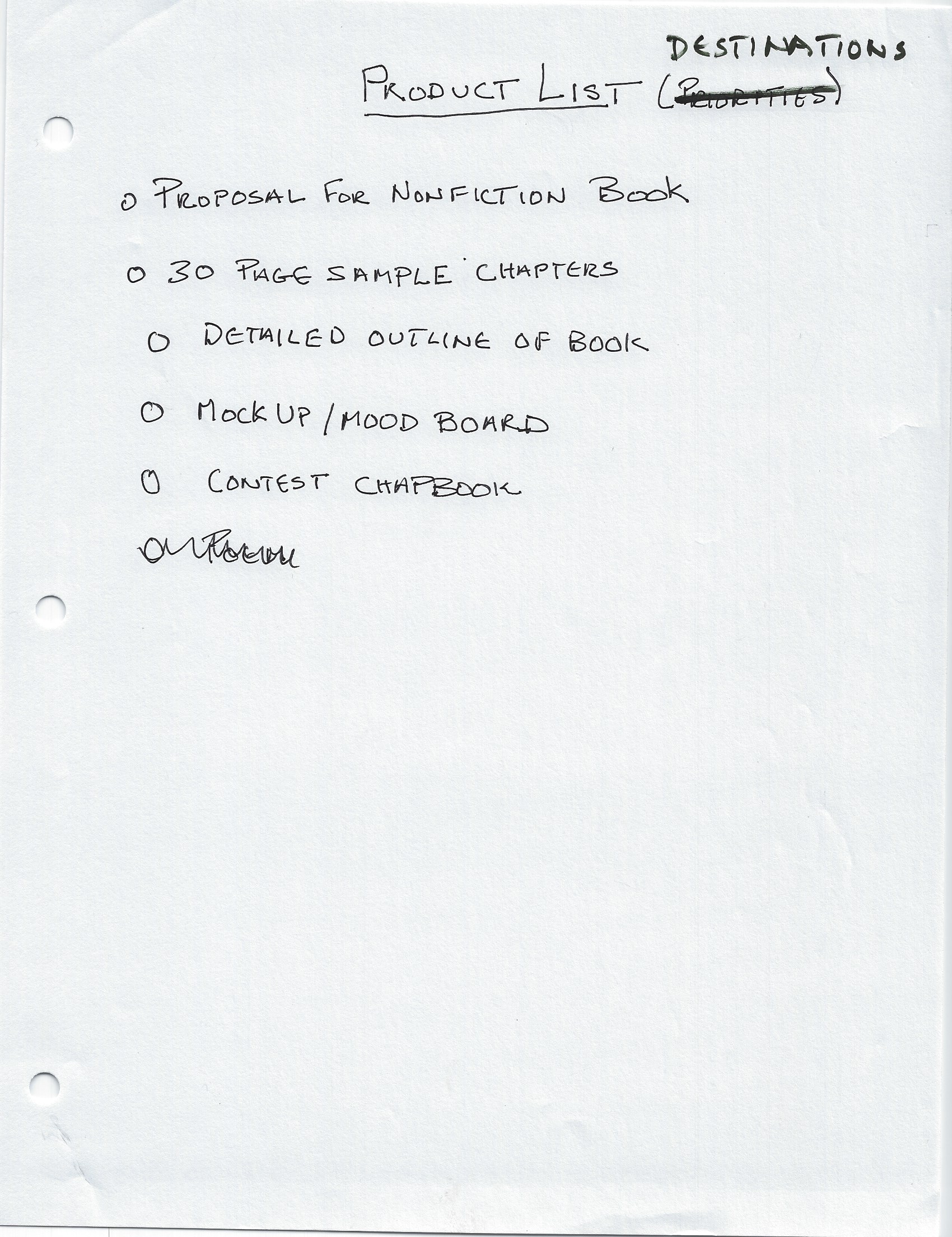

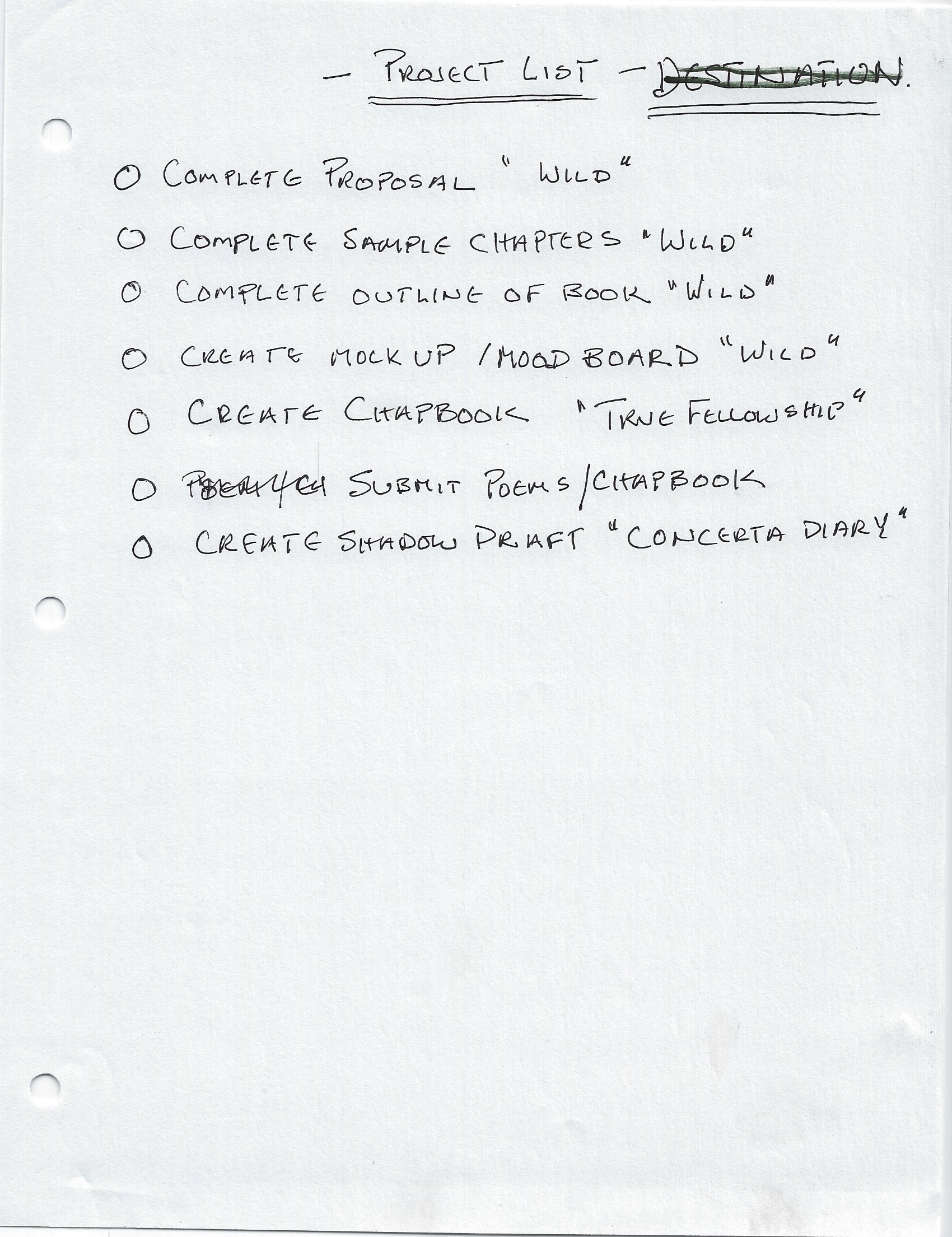

At the front of my project notebook, I keep a list of the priorities, products or goals I have in mind for that project period. The process of setting up my project notebook helps me clarify what they are. Sometimes those products, priorities or goals are texts, like a chapter, and sometimes, a process with an outcome, like a review of pertinent literature that will enable you to frame a problem, or tell a research story.

The products I list below are the outcome of a process that took several months of research, reading and notetaking– a different set of goals.

You’ll notice that I have “destinations” related to a book project, but you’ll see other goals as well. Over the next few months, I have to keep work on the book at the top of my priority list, but I want to keep work going on the other projects as well. In the past, I’ve gotten off track. My Project Notebook helps me prioritize.

Sometimes, it helps to do some writing to help you picture the goal you have in mind. Below are some exercises to help you clarify your products, priorities, or goals for the nest several months.

Getting Started: I used to…but now I…

Take out a sheet of paper. This will give me a chance to introduce you to a very powerful practice, one that’s very helpful and goes by many names, but which I’ll refer to as “free writing”. You’ll find guidelines for it in this document at this link. More resources for it here, including articles on its value can be found here. bit.ly/ResourcesforWriting

You’ll write for ten minutes without stopping exploring the following: how your thinking about the project process and your ideas have evolved over time. Use the generative sentence “I use to think… but now I think…” to get you started. To get started, you may write versions of the sentence and when you get stuck, you might return to it and rewrite it to clarify or extend your thinking. Most importantly, keep your hand moving. This is “stream of consciousness” writing, so the goal is to produce text, not pretty sentences or thinking for an audience. Reflect, ask questions aloud, talk to yourself, but be concrete and particular as you explore your thinking.

Setting out the Path

Take a sheet of paper, turn it the long way and fold it into thirds so that you have three columns.

Column Three: My Destination

Label the third column “My Destination”. Take a few minutes and describe the product as you envision it currently. Be as concrete and detailed as you can be, even if it means using your imagination to describe what you haven’t quite pinned down yet. You might consider the following:

- Describe the problem your work addresses or will solve

- Describe the form it will take, such as the number of chapters or sections

- Describe the method involved and the data you’ll be using

- Describe your stance and point of view

- Describe who you intend its readership to be

Column One: Where I Am Today

Now, label the first column “Where I Am Today”.

In this column, describe where you are currently with respect to that final product. You might consider some of the following:

- What have I written? Don’t be shy about including notes, journals, drafts, seminar papers, proposals for conferences, conference presentations– use any documents you think will contribute to the work you intend to do.

- What have I read? What data have I collected? Academic writing, especially dissertation writing, but also journal articles and other professional writing, situates itself in a body of current work. What is the status of your research in the respect?

- Where am I in the process? Consider the process with respect to you discipline and your department’s requirements, of course, but also with respect to the work as it is your own. That is, this is your project, you are the creator of something new: what is your current thinking? What problems have you solved or identified?

- What is the current status of your thinking? Where do you currently stand on the issues or problems you’ve identified?

Column Two: The Path Ahead

Label the second column “The Path Ahead”.

Considering where you are now and what you intend to create, give some thought to the following.

- What questions do I need to answer about the process itself, with respect to the institution, the department, or, if it’s pertinent to the project, publication?

- What questions do I need to answer about the form of the final product? Consider this from two angles– your goals for it as your creation, and genre or departmental requirements (for example, the form of other dissertations or the style used in publication)?

- What are the next steps in my research? This may include reading, data collection, data coding and collation and so on.

- What questions are open in your thinking? What problems do you have to solve? While you may be certain of the main claim of your piece, you may also have questions and “open loops” that must be addressed. What are they?

Back of the Page: Where Would You Like to Be At the End of The Term?

Turn this page over and consider where you would like to be on Friday. This is not an opportunity to set out extravagant goals or to establish a benchmark. Simply lay out what you hope you will have accomplished.

You might describe what you have created (a certain number of pages or an outline or whatever is appropriate to you project or discipline).

You might describe what you hope to have done (read a certain thing, taken notes, generated text each day).

You might describe what you hope to have explored or a problem you hope to have solved. (An idea you’ve been trying to hammer out, for example, or bug you need to debug.)

Envision Your Project: Project Lists

Excerpted from Getting Things Done, Donald Allen

The idea of a Project List comes from David Allen’s book “Getting Things Done”. The Project List is part of a two-step process. Once you compile a Project List, you use it to make a “Next Action” list for each Project on your Project List.

Allen writes that “A PROJECT LIST is a master inventory of your Projects” while a “next action,” is “the next physical, visible activity that needs to be engaged in, in order to move the current reality toward completion.”

Allen believes that a project list and its partner in the process, “Next Action” lists are more helpful, rather than a “to do” list or a list of next actions you generate as the situation calls for it.

One of the most common questions we get, as people begin to implement the GTD method, is “Why do I need to have a Projects list?” In other words, people want to know if they can get away with simply creating and looking at lists of Next Actions.

A current, clear, and complete projects list is the key tool for managing the horizon of our commitments that, in my experience, has the greatest improvement opportunity for anyone leading a life of any significant complexity.

Projects range all over the map, and most people have between thirty and a hundred such commitments, at any point in time. Each one of these agreements with ourselves needs some sort of “stake in the ground” anchored in such a way that we revisit it frequently enough to trust nothing is being missed or falling through the cracks about it, and that forward motion is appropriately happening. If you only tracked Next Actions, then once you finished the action, without a trusted placeholder for the final outcome, you would have to keep track of that desired result in your head.

David Allen, Getting Things Done

When I teach people to use these tools, I find there is sometimes confusion around the world “Project”. If you’re working on a dissertation or an article or a prospectus or an exam, you may think of that dissertation, exam, or prospectus as your “Project”. So, you might say to yourself, “Well, my project list has one project on it: my dissertation.” Allen developed these tools as part of his work as corporate consultant, where the term “project” encompasses many different activities that can include among other things, day to day operations, events, analyses, and products.

To avoid any confusion around the use of the world “Project,” I’d like you to think of your dissertation, prospectus, exam or article as a product, goal, or priority. That product is the concrete outcome of a process made up of many smaller “projects” that will ultimately contribute to its success.

Allen defines “projects” in the following way:

Projects are any and all those things that need to get done within the next few weeks or months that require more than one action step to complete.

To get started, you might brainstorm a list of projects, goals, or priorities. When I first set up the Project Notebook, I go back and forth between the Project Lists and Next Actions lists. The process helps me clarify what I have in mind for the nest few months.

Allen’s “Project” and “Next action” lists give me a way to hammer out and organize the steps I need to take to complete a project. The Project and Next Action lists become the basis for the daily “to-do” lists I create.

I return to the completed lists to help me see the practical progress of a project.

A tip: Try naming those projects using a Verb and a Noun. For instance, I might say, “Book Proposal” but I find it more helpful to think “Compose Book Proposal.” Even if you begin by listing nouns or phrases as I have in the bulleted list above, try and review your list and add verbs to those nouns and phrases to further clarify the project as an action that will contribute to your product.

Envision Your Project: Next Action Lists

Excerpted and adapted from Merlin Mann, 43 Folders

Create A Next Action List for Each Project

Next Action lists work in tandem with your Project List.

I create a separate Next Action list for each project. I put each project on a separate sheet of paper. I review them, typically weekly, and use to set my goals for each work session, or day, or week. Over time, I review and revise. Projects are completed, and new projects and next actions emerge.

Merlin Mann, whose blog 52 Folders is popular with free lancers contrasts Next Actions lists with To Do Lists.

Next action lists only hold your next actions.

For example, a classic old-school to-do might be something like “Plan Tom’s Surprise Going-Away Party,” “Clean out the Garage,” or “Get the Car Fixed.” But, as Allen cannily notes, these are each really small projects since they require more than one activity in order to be considered complete.

Learning to honor that distinction between a task and its parent project may, in fact, be the most important step you can take toward improving the quality and “do-ability” of the work on your list.

By always breaking projects of any size into their true constituent next actions–and it’s definitely okay to have several at once per project–we’re making it fast and easy to always know what should be happening next.

Next action lists enable you to keep putting one foot in front of the other, ensuring that you always know what to do next, instead of half-assing your way through a badly-defined pile of fuzzy nouns. This physicality and functional piece-work act in concert to make the planning and execution of your tasks as stress-free and un-intimidating as possible.

Merlin Mann

Instructions

Select a project from your list and write its name at the top of a sheet of paper.

Break the Project down into “Next Actions” for the project. Keep the following in mind. Merlin Mann writes that you should

Articulate your to-dos in terms of physical activity–even when they require only modest amounts of actual exertion. To do so ensures that you’ve thought through your task to a point where you can envision how it will need to be undertaken and what it will actually feel like once you’re doing it. This means you can easily visualize the activity, the kinds of tools you’ll need, and perhaps even the setting where the work should take place.

Get the verbs right. Notice how we’re breaking these Big Nouns into little verbs?That’s deliberate.With that original to-do for your presentation, you might theoretically just keep “preparing” your presentation until some arbitrary alarm bell goes off in your head, saying “Yeah, okay, that looks like a fully-prepared presentation, so you can stop.” But a better-defined chunk of activity suggests a task with clear edges; it has a beginning and an end.

- Try phrasing your task in a form like:“verb the noun with the object.”

- Not “Year-end report,” but “Download Q3 spreadsheet from work server.”

- Not “Meet with Anil,” you’d probably want to “Email Anil on Monday to schedule monthly disco funk party.”

- Whittle the task down to one activity that you can accomplish completely at a sitting.“A sitting” will vary for you, but I try to never plan a task that would take more than ten minutes (your level of busy-ness might command even smaller-sized tasks).

Using Time: The Writing Session

On the first day of the Boot Camp, we don’t spend much time talking about what you understand “writing” to be. People have often asked me about how to manage their writing sessions. You have a good deal of uninterrupted time, which in itself can become an obstacle to producing work. Some people find themselves lost in that time, uncertain about what to choose to do. The work itself can be exhausting.

Below are some suggestions for how you might use your day.

Suggestions (These suggestions are based on what writers have shared with me, as well as what I do. In fact, I’ll begin with a description of my own practice. Results will vary.)

Break Sessions into Small Work Sessions with Breaks

Many people are familiar with the concept of “Pomodoro” time—25 or 45 minute blocks divided by breaks of five or ten minutes. You set your goal for that period of time (not necessarily what you will produce, but what you intend to do). Then, set a timer. When the time rings, take a break—stretch, have a snack, read your email, check the news. Then, begin again.

Start and end each day with your “accountability” group.

We’ve discussed the guidelines for you group. In the morning, the group will help you clarify your goals and establish your intentions for the day. At the end of the day, the group can help you identify what went right in your process and what you want to do tomorrow.

“Morning Pages” or “Non-Stop Writing”

I have made Julia Cameron’s morning pages a part of my writing practice for some time now. These pages are a form of nonstop writing. Cameron offers a description of the practice in your book The Artist’s Way, where they are part of her approach to helping creative work happen. If haven’t done these pages before the work day begins, I make sure I do them when I sit down to begin a work session. They are the first thing I do if I haven’t done them already. Cameron suggests writing three pages of stream of consciousness writing. Once you’ve done them, you set them aside.

Work Log: Review my Next Action Lists, Identify my Goals and Block Out Time

Give my particular ways of getting lost and distracted, I’ve made a work/research log a part of my daily practice for the last several years. When I start work for the day (and this includes a typical work day in which I’m trying to ensure that I make space for my creative work in the context of my everyday employment and family obligations), I review the time I have available and decide how I will use the time.

I keep this log for two reasons. It enables me to review my progress and can help me identify obstacles.

Over the last few months, I’ve done the following. I use a regular composition notebook and on one side, write down the hours of the day, beginning from when I wake up to ten o’clock, with an hour per line.

I block time out that I know is committed first—for instance, your group meetings at the beginning and end of the day and lunch.

On the opposite side of the page, I set up categories based on my next action lists, which I review to help me set goals.

Then, I return to the time I’ve laid out on the other side of the page, and sketch in what I intend to work on throughout the day at specific times.

Then, I’ll write a “memo” to myself that lays out what I intend to do in the form of a journal entry. I make time at the end of a work session to return to this log to note what I’ve done, what might have gotten in the way, and to review how I felt about the work that day.

Write in Your Research Journal

It can be very helpful to have an open-ended journal where you reflect on ideas as they come to you, and on the process as it evolves. I have done this is different ways at different times—sometimes I write in a google doc, or a private word press document. Sometimes ideas emerge in my work log. Although I use the log primarily to keep track of how I use time, ideas emerge there to. But I think of my research journal as a place where I write in expansive ways about my ideas: it’s a home for speculation.

Create, review and update a topic list

At the back of my research journal, I keep a topic list. As I work throughout the day, if a topic idea comes up, I enter it into my topic list, which I can then use later to start writing.

Notecards

These days, I keep a stack of notecards nearby as I work. What I write in them won’t get lost in long lists of pages (something that’s happened in the past). I write quotes on them, ideas, stray thoughts and bibliography entries. Periodically, I’ll review the stack.

Create an Annotated Bibliography

When you’re trying to write a long project that depends on the work of others, becoming fluent in their thoughts is important. Writing straightforward annotated bibliography entries for the books, articles, and other documents you’re relying can be helpful. You may do simple one sentence summaries, or something lengthier, such as a two hundred word entry that identifies the authors, summarizes the main points, and puts the work in the context of other work or your own.

Timed Writing

Nonstop writing can be a very helpful part of the process of completing your project and your overall practice as a writer. This document and the resource site contain guidelines and writing about non-stop writing. The practice is highly adaptable. You can write to a topic or write in an open-ended way. At first, you might start with five or ten-minute sessions and as you build up confidence in your ability to produce words this way, extend the time.

While working on my current project, I did the following. I wrote in twenty-five minute blocks.

I would choose a topic or a task, such as summarizing and interrogating a chapter I’d just read. I had some rules I followed. Once I began the twenty-five minutes, I’d write until they were done. Anything that came to my mind went into the writing, even if it was personal or off topic, but periodically, I would bring myself back around to the topic at hand by repeating myself or restating the frame that started the whole thing. Since one of my goals has been to become more fluenct in some unfamiliar ideas, I allow all restatements and repetitions. At times, I might type up sections of text—lengthy block quotes—particularly if my goal is to learn to speak new ideas in my own voice. Typing these quotes out would become the basis for summarizing and reflecting on them.

Later, after I print out the text, I will annotate and cut and paste into relevant sections and categories to create a draft.

Create Visual Representations or Concept Maps

In this document you’ll find some guidance on this this, but you might also acquire the book “The Sketch Notes Handbook” to give some thoughts on how to create graphic representations of your ideas. These can be very rich and can also allow you to see the whole before you embark on writing text. They then can become a guide to the work as it unfolds.

Attend to Practical Details

PDFs need to be downloaded, bibliographies updates, appointments made, work proofread. Alternate time that you spend concentrating on drafts and reading and ideas with practical matters.

Walk!

If you find yourself stressed or blocked, or find your mind wandering—take a walk outside, get some fresh air, and return. Ten minutes is plenty to re-boot your attention.

Write Letters

If you find yourself in a bit of knot about what you are doing or trying to say, write a letter to someone you trust or fee confident with. Explain what you intend to do as plainly as possible.

Write with a Group

You might consider doing a half hour of non-stop writing with a group of fellow boot-camp folks each day, perhaps during a time when people tend to flag, like the middle of the day. Get together for a half hour and write for three ten minute sessions.

Structure of a Writing Accountability Groups

Sherry Anne Roquemore, Shut Up and Write!

https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2010/06/14/shut-and-write)

Overview

If your primary need is to have a committed group of people to answer to each week, then writing accountability groups may be worth trying.

Developing a daily writing routine tends to bring up all people’s stuff and the group helps to support one another by identifying the limiting beliefs and behaviors that hold members back from productivity. Nobody reads anyone else’s writing in this type of group. Instead the focus is on the writing process and moving projects forward so they can get into the hands of people with subject matter expertise (not group members). This structure works well when the primary needs of participants are accountability, support, community, and peer mentoring.

Instructions

The structure is fairly simple. Group members meet at an agreed upon time, such as the first fifteen minutes of the bootcamp morning and the last fifteen minutes of the day. People have also checked in with one another at the beginning of the afternoon.

One person at a time reports on the following:

- my goals for _____ were _______,

- I did/did not meet them,

- if I didn’t meet them, it’s because of _______ and

- my goals for _______ are _______.

Free or Nonstop Writing

Overview

Free writing can be a practice that starts a writing session or something to do when you are at a moment in a draft when you’re are not sure which way to go. You can use the practice to generate text, or as a part of a daily reflective routine.

The core of free writing is not necessarily when or why you do it, but how you do it and the principle and habits of mind involved.

In free writing, you fill time, not space. Often, when we think about writing, we think of a number of words or pages. Here, your goal is to write for the allotted time without stopping. You write with out attention to the outcome– your goal is not stylish prose or fully realized ideas. The principle here is that if you suspend judgement and allow yourself to think through your ideas and how you express them on paper, you are more likely to realize your writing goal and, over time, develop a voice that recognize more as you own.

Free writing helps you to practice, and perhaps adopt, some helpful creative academic and writerly habits of mind: suspend judgement to generate material, work with materials to find ideas, lower expectations to facilitate composing, compose freely and without restraint when generating ideas.

Guidelines

Choose a topic or a prompt to help you begin to write, keep you going and focus your writing. You can simply begin writing, if you like, or start with a key word, a question, a vague notion or a concrete problem.

Decide on a fixed period of time and set a timer. You can begin with five minutes and increase from there as you see fit. Remember to end when the timer goes off. It can be good for your confidence over time to know you can end and begin again.

Keep you your hand moving. Don’t stop to reconsider or to polish. If you feel you want to say something differently, don’t erase. I would say it will be more helpful simply to repeat yourself differently. Remember that the idea is not to create perfect prose. Rewriting is an important process. This process puts the clay on the table you’ll work with later.

Follow your thinking. If you find yourself distracted by a line of thought, follow the direction it takes. Explore your ideas.

Be concrete. Be particular in what you describe.

Speak freely. Allow yourself to write without the expectation that you will say what you want perfectly. Repeat yourself, if you’d like.

Practice setting judgement aside, with respect to style or your thinking. As many have said (in many different ways), you must write badly to write well.

Get up and walk away. Sometimes sessions are lousy, sometimes, routine, sometimes marvelous. Since there is no way to get this wrong don’t bother yourself with thoughts like “I hope I did this right. My writing isn’t free enough. I mostly wrote the the the.” Just come back tomorrow.

A Note on Routine

Many have that some form of free writing routine helps– it is a way to practice some simple, helpful writing habits of mind: suspend judgement to generate material, work with materials to find ideas, lower expectations to facilitate composing, compose freely and without restraint when generating ideas.

Experiment with a routine. Some do this daily. Elbow suggests at least three times a week.

A Note on “Being Stuck”

Recently someone told me that she tried to free write upon my advice and found herself stuck with herself– anxiously perseverating, pawing over something that embarrassed her or some negative experience or self-assessment. I understand this and there was a period of time when I free wrote extensively and this was very much the case for me and very painful. So I have given this a lot of thought.

In a meditation practice, such as meditation on the breath, where a meditator while practice awareness of the breath, when her mind wanders or a line of thinking takes over, the practice is to become aware of the thought, to see it without judgement– not to try and stop it or criticize oneself for thinking, which, after all, is what minds are meant to do– but to return to the breath. It is hard to do. The meditation teacher Jack Kornfield has said that it is like training a puppy. The puppy wanders away and you bring it back. I have found that difficult in non-stop writing, since I am thinking on paper and my thinking is the think I am attending to. I am trying to keep myself writing. But when my writing becomes a rehearsal of my fears, misgivings, doubts, and uncertainties, when I am behaving ungenerously toward my life, projects, body or self, I am no longer free writing, I suppose. I am now doing something else more again to writing “I will always do as I am told” on the blackboard a thousand times.

I have a couple of suggestions. One is to simply stop and have that be okay. It would defeat the purpose of the practice to judge the experience or the outcome. But I have tried other things as well. I began to think of this perseverating as a form of “stuckedness”. When I am stuck, I turn to the concrete. I look around and describe what I see in my physical environment. I describe my physical state. I name what I am doing directly: you are anxious right now about what so and so said. That’s difficult. What are your plans for dinner tonight? Again, by being concrete and turning my attention to something benign that requires focus, it interrupts my attention to something that often, but not always, turns is forgotten as I re focus.

Diaries, Logs and Journals

Keep a Project Diary, Log or Journal

One way to learn about what works and what doesn’t when it comes to writing is to keep a project diary, log or journal. These are spaces where you keep a record of your work and where you reflect in an open ended way on your project. Over time, a narrative of your project emerges. A narrative of your way of working also emerges.

You cultivate a vantage point on the design of your project that allows you to choose among possibilities. You also get to know yourself as a writer.

You might think of an entry in your log, diary or journal as a way to start each a work session. Start a session by writing what you intend to that day or morning and simply return when the afternoon session begins or at the end of the day to review what you’ve done and set your intentions for the next session.

At the start, write down the day, time, and place.

- Answers these questions:

- What do I want to accomplish in this time at my desk?

- What tasks did you complete the last time you worked?

- Which tasks carry over?

At the end of the session, note how long you worked and answer these questions

- Did I accomplish what I intended?

- What is left over?

- How did I feel about the work?

- If I didn’t complete the work I intended, what got in the way?

You might continue with an open ended reflection on the work you did and your project. Remember, though, this is not a space for judgement and self-criticism. Your approach should be more along the lines of observation than evaluation. Let it be a place where you are getting to know yourself as a writer.

Graphic Representations

Diagram Legend

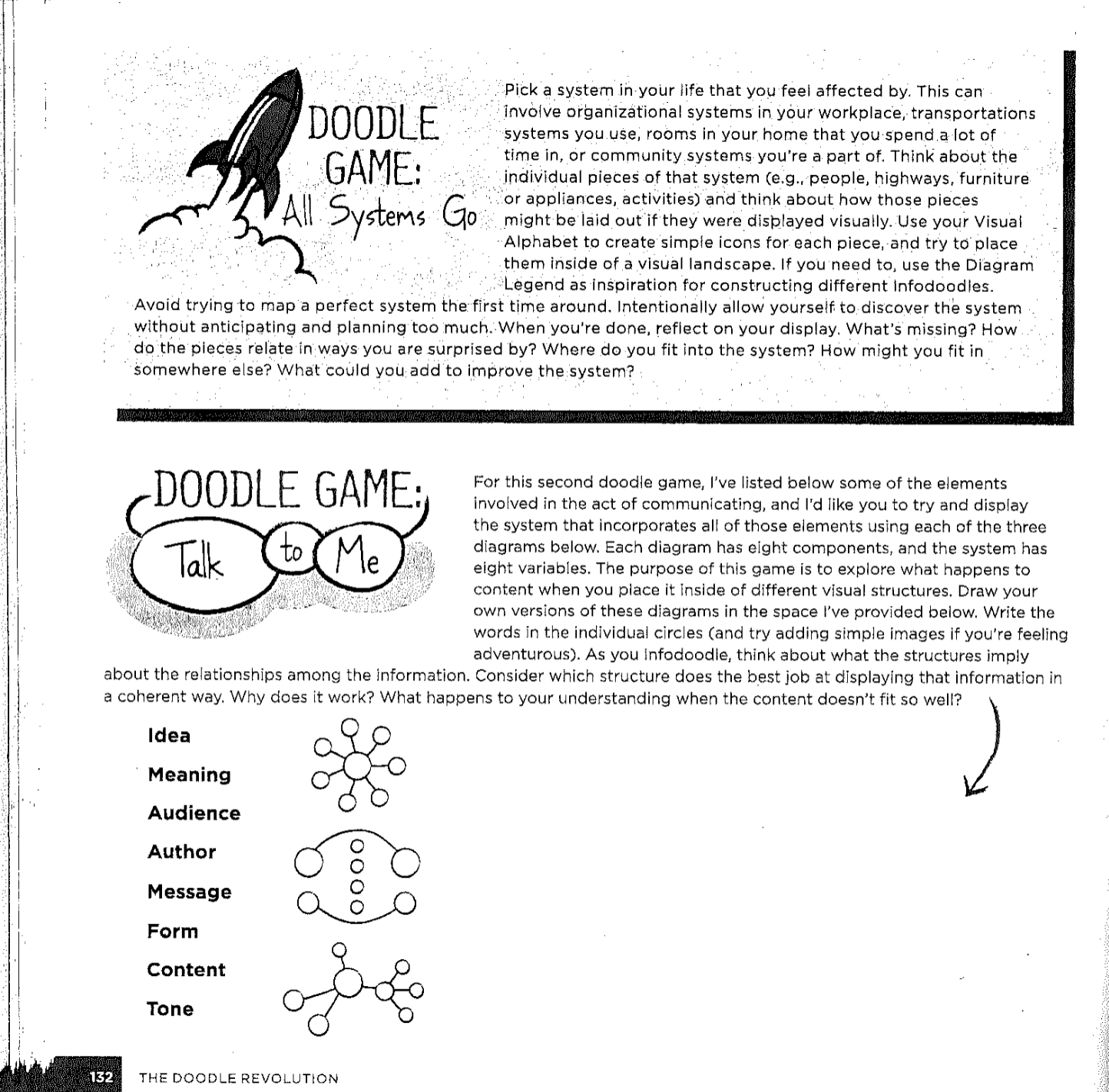

Comparison Game

System Game

Process Game