If My Life Was a Shape

How do you get to a piece of writing that you share with someone from an idea?

Write to explore the idea.

Put aside ideas about “good” and “bad” writing is. Put aside any uneasiness you have about how others may regard your writing. Right now, you are gathering and collecting.

Test your idea, tease it into shape.

You may need to find what you mean. You may need to make what you mean.

Even if you know exactly what you want tell us, take time to discover how to bring that idea to life in our minds.

So before you write something with us in mind, enjoy the privacy of your own mind.

Here is an exercise to help.

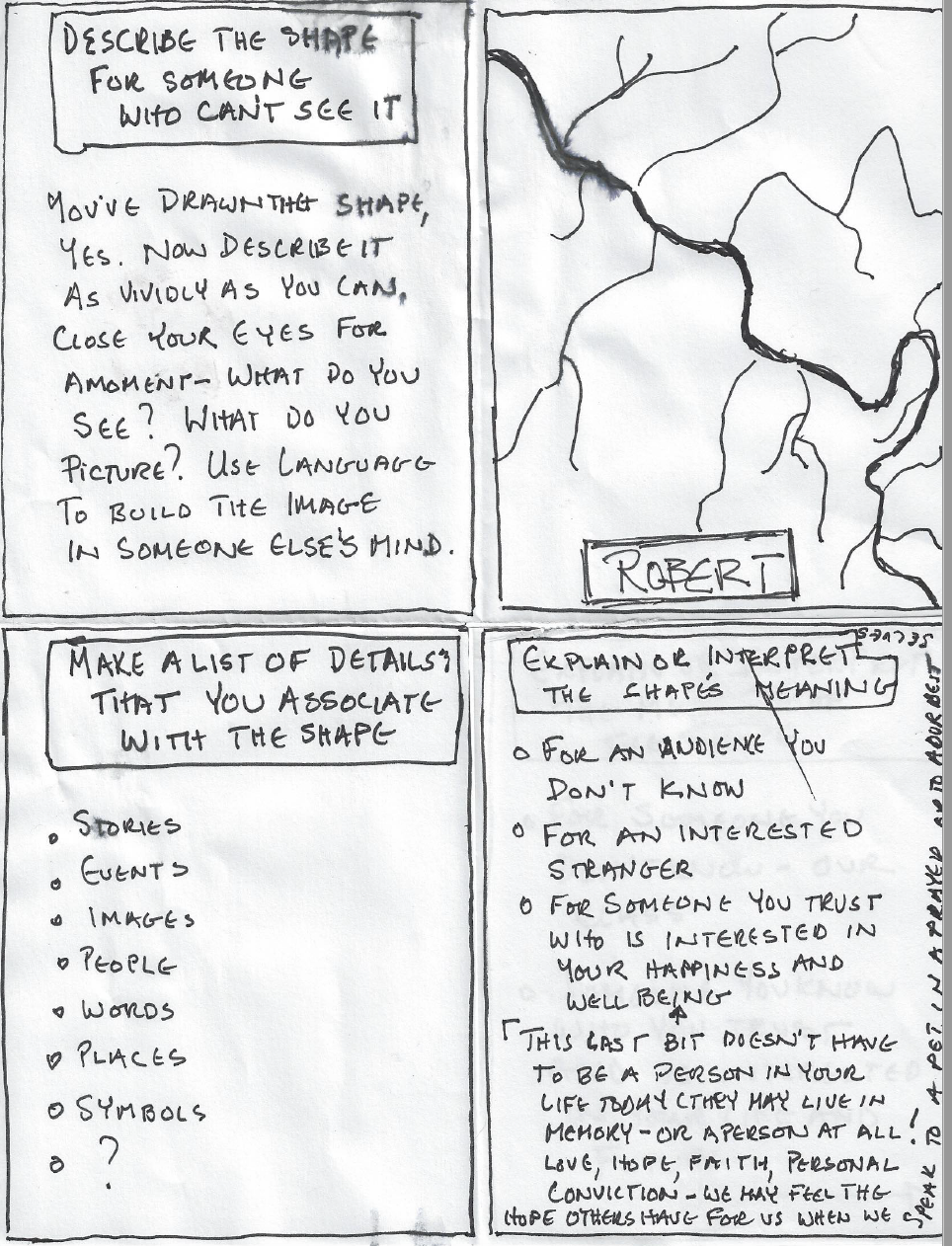

- Fold a piece of paper in half from the bottom to the top of the page.

- Then, fold the folded page in half from left to right, like a book.

- On the “cover” draw a frame. Within the frame, draw the shape that comes to mind when you answer the question, “If my life had a shape, what would it be.”

- Now, open up the page so the picture is on the top left.

In the box to its right, describe the shape for someone who can’t see it.

On the bottom half of the page, starting with the box on the left, list of details that you associate with the shape. List stories, events, images people word places, symbols. No matter how disconnected, or surprising, or mundane, list what comes to mind when you think of the shape. See what happens if you walk away at this stage and leave the page open on your desk, or carry the list in your pocket and check it every so often.

Finally, in the last box — and you may decide to go on to the back of the page– describe your shape for an audience. Try one or all three.

- First, for an audience you don’t know.

- Then, for an interested stranger– someone you sat next to on a bus or a plane (many great stories begin with a stranger sharing a tale on while traveling.)

- Finally, describe the shape for someone you trust. Think of someone interested in your happiness and well being. This may be a person who lives in your memory. It may not be a person at all. You may feel the hope others have for you, and the hope you have for yourself, your sense of faith and personal conviction when you’re alone and speaking to a pet, or sitting in nature, or talking a walk.

Now that you have some clay on the table, put aside any idea of what “good” or “bad” writing is. Put aside any uneasiness you have about how others may regard your writing. Try not to worry how you sound.

Don’t spend too much time. Use what you’ve gathered to create a short piece of writing. Shape it. Touch it up lightly perhaps. Think of it as by necessity unfinished. Set it aside for a bit. Come back to it. Come back to it again: Ask yourself, have I said at least mostly what I meant?

If the answer is “Yes,” post it on our blog with the picture of your life as a shape.

Observe: Zoom In/Zoom Out

Part One: What Am I Observing For

When I observe nature– and by nature– I mean, usually, the nature in my apartment or outside my window– I’m rarely moved to answer the questions I have. Why are spiders always in the bathtub? Where do fruit flies come from? Why does a bat fly that way when it’s trapped? Why have I never seen a cockroach in Ithaca? I used to see them all the time in the City. But I notice: the woodpeckers are back. There go the geese. That spider has long legs and one long leg like thing that probes. It doesn’t have a body or a face, just a red disk its legs are connected to.

Although I couldn’t tell an ash from an oak, and almost never know the names of flowers, when I look at nature, I’m using my eyes to see and take note. I can follow the tree from its roots up the trunk through its limbs. I have a language of description that’s everyday: in a way, we all are folk naturalists.

It can be more of a challenge to learn to make observations of essays that can help us understand how they are made. We wonder, what is there to observe? What should I notice?

But when we read as writers, we can trust one thing. The person who wrote the essay made the essay out of words. They made choices. They read other essays. This week we read Samantha Irby and Eva Babitz. Each told private stories to us. Perhaps you said to yourself, “Yeah, I like that. I can relate.”

But we say “I can relate” all the time. After all, I’ve had conversations about money, bills, and parents with friends and they’ve said– “Wow, me too.” I’ve talked about the gender roles I dealt– expectations for what a boy or man needed to be or do and heard people say, “I can’t relate, but I can understand.”

Somehow, though, Babitz and Irby accomplish something just as Gay, Ginzburg, and the others we read do: they come alive as speakers and they capture our attention as an audience.

Sometimes, a writer’s work can seem effortless, especially when the writer’s voice seems so clear and strong and conversational. But that voice practiced and crafted. So, the essay is also a kind of performance. We follow the flow of thought, we see, hear, sense and follow the energy of the piece, its stops and starts, interruptions and rhythms. The writer controls your attention.

That performance is predicated upon a relationship that the writer creates with us– the reader. The “you” in Irby’s case. The person to whom Eve Babitz is speaking who might “relate.”

Sometimes they describe something for us or they tell us a story. And sometimes, they stop to explain what they mean.

In the back of you mind as you observe, hold these questions in the back of your mind:

- How did she do that?

- How did she get from there to here?

Part Two: Zoom in/Zoom Out

One strategy you can use when you are reading an essay– any piece of writing, really– is “Zoom In/Zoom Out.”

You an Zoom In to individual words

“Liliocalani and Nefertiti” (the names of Eve Babitz’ cats in On Being a Tomboy are the names of two great queens)

You can Zoom In on phrases

our snarling-German-shepherd-chained-to-the-garage, Chevy-caprice-on-blocks-in-the-yellowed-front-yard-suburban home (Samantha Irby uses hyphens to create “names” for what neighbors see and hear, names that evoke the conflict between her parents– noise, anger, neglect. Why a German shepherd? Why chained? What do you see and hear? Why a Chevy Caprice on blocks? What do you see and think?)

You can Zoom In on sentences and take note of how the writer built them and how they move.

After they shook hands amicably, Mom excused herself, collected me from the bathroom where I was trying to drown my Barbie dolls in the tub, then drove straight to the bank to withdraw all but one dollar from my parents joint bank account. (Irby starts with “amicably, excused, and collected,” then, detours into a disturbing scene played for effect — the child Samantha responding to overhearing her parents in the kitchen, the a “straight” drive– calm and purposeful. The sentence starts with an amicable handshake and ends with her mother “withdrawing all but one dollar from my parents joint bank account.”

You can Zoom in on a moment.

I have no idea how people who actually have money talk to their children about it. But I sure as shit can tell you how poor people do.

The very idea of the word “tomboy” enraged me when I found out about it. It was such a stupid trap.

These are the first sentences of “Do You Guys Pay Your Fucking Bills or What?” and “On Being a Tomboy” respectively. We already know he subject of the essays from the titles, but here, we get the writers voice and stance. What are we getting? And how does that voice continue throughout? And who are they talking to?

You can Zoom In on white space, graphic elements, and other features of design like bullet points and headings, then Zoom Out to ask how those features function as part of the whole structure, or the relationship between the writer and the reader, and the writer and the subject matter.

You can Zoom Out and consider a paragraph as a whole, how it moves, what it includes, and the effect it has.

The very idea of the word “tomboy” enraged me when I found out about it. It was such a stupid trap. Either you were a “girl”– sugar and spice– or you were a “tomboy” puppy-dog tails. The idea that they only had two categories and those were they turned me white-hot. With silent, guerrilla impatience, I sat alone in school in Hollywood feeling like Che in a business suit, walking through the city of Havana before he got rid of Batista. I couldn’t wait to get out.

You can Zoom Out from the paragraph and look at the structure of the whole piece. Ask yourself:

This is the first paragraph. This is the last paragraph. How are they the same or different. What can she say at the beginning that she couldn’t in the end? How did it begin? Where are we left?

You can Zoom Out to follow the way the piece is structured from paragraph to paragraph or section to section. Does it

- seem to follow the unfolding thoughts of the writer? If it does, how does it get from place to place?

- seem to be organized around time, like a story, events happening in a certain order, or as a process or procedure, where one thing happens before another.

- seem to be organized the way you might look at an object in space, first this feature, then another feature, or one side and another. Or the way you might describe categories of things, or organize them, or break a thing down into its component parts to explain them.

If you Zoom Out, you can trace the rhythm of a piece, because rhythm happens over time, and it requires patterns and interruptions of them.

If you Zoom Out, even further, you can consider how this text reminds you of other texts that sound the same, or look the same, or tell similar stories. What other texts use bullet points and subheadings? Who else talks about about being trapped by roles that seem arbitrary and oppressive?

If you Zoom Out, you can include the writer and the reader and their relationship. You, to a certain extent, are summoned by the writer, and are created by the writer. On the other hand, your interaction with the piece brings it to life, and takes on a life the writer might not have anticipated.

Observe: March to December Models

Overview

The March to December Project documents and explores the world you’ve found since the Pandemic began. We’re using December as an end point for the period of time you’ll document and explore because it is the end of this first, unprecedented semester.

The essays were studying provide us with many ways to approach the topics you decide to write about and you’ll be using them as “generative structures”– launching points for writing of your own.

You will decide what to write about and how to write about it. But you won’t be alone. This is an editorial process. We to bring our vision into focus. We will work together, asking each other questions, searching for ideas, and choosing forms. We will develop lists of topics to try, questions to answers, and things to remember.

- Are there things we want to remember?

- Are there experiences that we want to write about?

- What do you want to leave behind, to record, to share?

I want you to keep the following in mind.

- A process has happens over time. It goes throughs stages, repeats itself, and often returns to one stage again and again. Our work on Tuesday, when we read, is a process: we are learning how to read an essay.

- A project has a beginning, middle, and end. While you may use the same process over and over to create a project, the project itself starts, goes through a process of development and decisions until, finally, it is finished. We can repeat a writing process on several different projects, but the projects themselves, once finished, we leave behind.

Our project has these phases:

- Use models to identify a “container” for the project. What could it look like? What could it include? What could its elements be?

- Start the story development process. What topics could we write? What should we cover or include? What genres or forms can we include?

- Continue the story development process. What do you want to write about? What topic or subject or element do want to explore? What form do you want it to take.

- Continue the story development process. Submit a proposal for your part of the project. Review it with your team.

- Compose a draft. Receive feedback.

- Revise your part of the project.

- Submit your piece for review by your editorial team.

- Assemble the project for publication.

You are part of a project team, an editorial board, and we will begin this process together. This process is a design process, which means that we will constantly ask questions, create prototypes, produce models, and try out solutions on the way to finished project. As the semester goes on, your contribution will become clearer.

Step one, though, is to decide on what the project will look like.

Homework: Thursday, September 17: Use Models to identify a “Container”

We know these things to start.

- The essays we read are meant to be models and inspirations.

- The publication will be digital, so you can combine image and sound.

We’ll face many very common writerly problems such as

- What should I write about?

- How should I write about it?

- How will I know when it’s done?

At the moment, though, we’re going to start by looking at model “publications”. We’ll look at the “container” so to speak, first, and then think about what ours might look like, and what it might contain.

You have been assigned one common site to look at, and one site as part of your discussion board group. Please look at the assignment schedule for Thursday, September 17.

In your project notebook, follow our typical observation routine for our common site, which is called “Stories from the Pandemic” and the site your group has been assigned.

- What is my initial response?

- What is the source of my response?

- What do I notice?

- What do I wonder?

- What does it remind me of?

Your task here differs from the task you undertake when you ask “How is this essay made?”

When you ask, “What do I notice” Zoom out and look at the structure of the site. How do readers navigate through stories? What kinds of elements are used? Who are the writers? What kinds of topics? How long are the stories? Do they use images, sound, video.

Your goal, when you meet your group, is to report what you’ve observed. You should, quite literally, think of yourself as scouting out a new territory or neighborhood– what do find. Bring back what you learned.

In class on Thursday, you’ll be assigned a team. Together, you’ll review what each of you has learned and then make an informal presentation to our class to start the this phase of the project. At the end of this phase of the project, we want to answer the following questions:

- What will the project be like: audio, video, text, etc.

- How will it be organized?

- What topics will it include?